2025 Year-End Summary: Four Trends and Five Representative Works of Innovation in LLM Inference Systems

Introduction: The First Year of Inference Explosion and the Hundred-Billion Cost Battle

Looking back at 2025, we not only experienced technological iterations, but also witnessed a dramatic shift in the industrial landscape. If the past few years were an arms race of “large-scale model training,” then 2025 was undoubtedly the first year of “inference business explosion.” As model capabilities matured and Agent applications landed, the balance of cloud computing power fundamentally shifted: currently, the vast majority of GPU/NPU resources on the cloud are occupied by inference workloads. The scale of accelerator cards serving inference is often several times larger than that of training cards, and in some companies even an order of magnitude larger.

For any AI company, the largest cost center is often AI Infra. Within the territory of Infra, as user volume surges, inference costs take an overwhelming share. This means that optimizing the efficiency of inference systems is no longer just a challenge for tech enthusiasts; it is the “lifeline” directly tied to enterprise survival and development. Imagine, if through system architecture innovation, we could double inference throughput on the same hardware scale; for a tech company with massive compute investments, this could correspond directly to cost savings of tens of billions of RMB.

It is precisely this tremendous business value and technical challenge that drove our team to continuously explore the boundaries of inference systems over the past year. In 2025, we witnessed DeepSeek-V3 pushing MoE to the extreme, saw Agents evolve from demos to complex production environments, and experienced Context Caching transforming from a “slaying-the-dragon trick” to a “mainstream commodity.” As traditional inference system architectures (such as early vLLM and TGI) began to show fatigue and the marginal returns of single-point optimizations (Kernel Fusing, Quantization) declined, system-level architectural overhaul became the new growth engine.

This article reviews the four key trends driving our inference technology innovation and provides a detailed interpretation of our five most representative works in 2025 (SparseServe, Adrenaline, TaiChi, DualMap, MemArt), in the hope of offering a substantial technical response to the community.

I. Four Key Trends Driving Innovation in Inference Systems

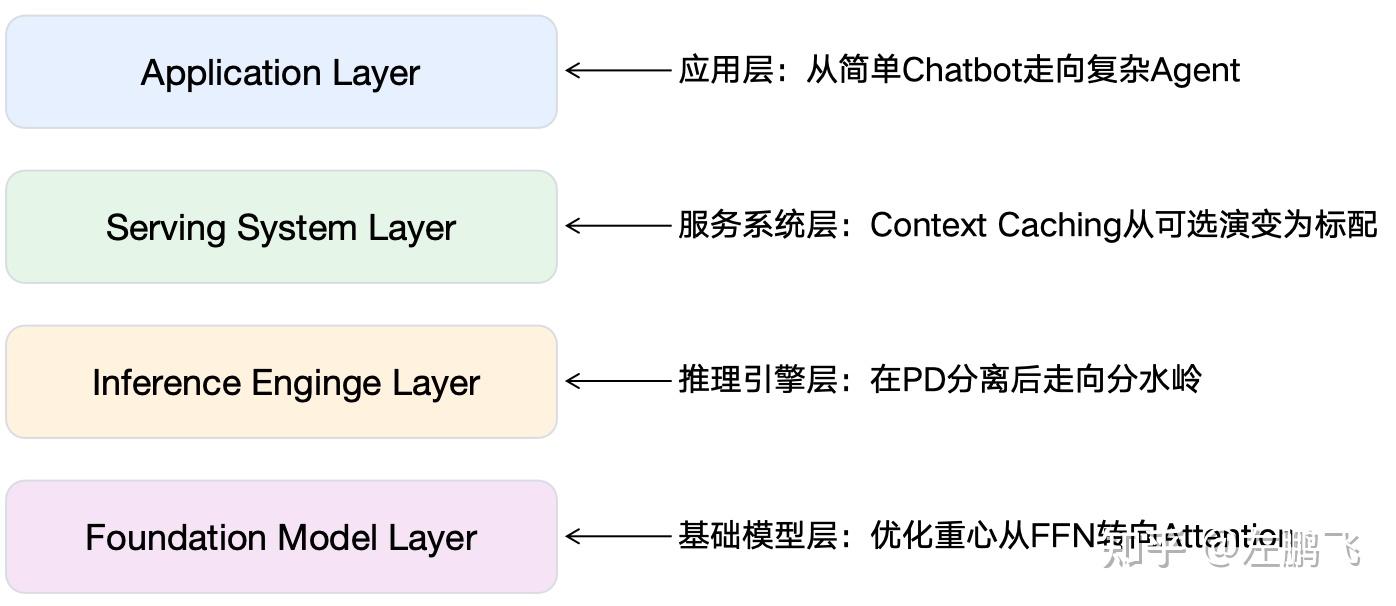

Before introducing specific works, it is necessary to first revisit the “wind direction” we observed this year. It is these underlying changes that determine why we pursued these research directions. As shown in Figure 1, I map these four trends to the four layers of cloud inference services.

Figure 1: Four Key Trends Driving Innovation in Inference Systems

Figure 1: Four Key Trends Driving Innovation in Inference Systems

Trend 1: Application Layer — From Simple Chatbots to Complex Agents

Phenomenon: The form of LLM applications has undergone a qualitative change. In 2023–2024, the mainstream workload faced by inference was chatbots (e.g., ChatGPT). These applications feature relatively balanced inputs and outputs, usually in the same order of magnitude (e.g., between 3:1 and 1:3). But in 2025, LLM applications evolved into complex Agents (e.g., DeepResearch), featuring a closed loop of “planning — tool invocation — execution — reflection,” continuously reading environmental information, invoking tools, and iterating decisions across multi-step tasks. This causes the Input/Output Token Ratio to surge to 100:1 or even 1000:1.

Challenges: 1) Prefill dominates: end-to-end latency and cost are no longer determined by Decode, but by Prefill. 2) Memory becomes a key factor: Agents need to “remember” user preferences and state across tasks and sessions. How to effectively represent, manage, and retrieve these memories to improve inference accuracy and efficiency becomes critical.

Trend 2: Service System Layer — Context Caching Evolves from “Optional” to “Standard”

Phenomenon: In multi-turn dialogues and Agent workflows, the prefix repetition rate of online requests increases significantly: system prompts, tool descriptions, fixed templates, and session context repeatedly appear within the same task chain. Each time doing Prefill from scratch directly translates the high input-output ratio of Agents into repeated computation and high cost. Therefore, Context Caching (prefix caching) has become a standard feature among major vendors (OpenAI, Anthropic, DeepSeek, Google, etc.).

Challenges: Caching introduces “state.” In the era without caching, requests were stateless; schedulers could freely dispatch requests to any idle node (Round Robin or Least Loaded sufficed). However, after introducing caching, to achieve cache hits, the scheduler needs to send requests to the specific node holding the prefix data. This is called Cache Affinity. This leads to the most thorny “affinity vs. balance” contradiction in distributed systems: 1) Pursuing affinity can lead to overload of nodes holding popular prefixes (Hotspots), creating long-tail latencies. 2) Pursuing balance by forcibly scattering requests prevents cache reuse, wasting compute resources.

Trend 3: Inference Engine Layer — Optimization After Prefill–Decode Separation Reaches a Watershed

Phenomenon: Early LLM serving often adopted PD coupling, placing Prefill and Decode in the same resource pool, squeezing resource utilization through batching, scheduling, and operator optimization (e.g., Orca). As inference services began simultaneously constraining TTFT/TPOT, the industry gradually shifted to PD separation to reduce latency interference between Prefill and Decode.

Challenges: After PD separation, “double waste” of resource utilization emerged. Prefill side has busy compute but underutilized memory capacity and bandwidth; Decode side has KV staying resident leading to tight memory capacity and bandwidth, yet compute is underutilized. Hence “low resource utilization” becomes the key contradiction. At this point, inference engine optimization reaches a crossroads: 1) Heterogeneous deployment: e.g., run Prefill on cards with strong compute but weak memory, and Decode on cards with weaker compute but stronger memory. Along this line, one can even further split the Decode’s Attention and FFN (AF separation) and deploy onto heterogeneous cards to continue to improve elasticity and utilization (e.g., MegaScale-Infer). However, in cloud data centers, heterogeneous deployment often encounters issues such as the unavailability of heterogeneous resources, difficulties in high-performance network interconnects, and reduced elasticity. 2) Separated mixed colocation: logically still separated, but along the execution path cross-stage mixing, e.g., co-deploy compute-intensive and memory-intensive inference sub-stages on the same card to improve resource utilization.

Trend 4: Model Layer — Optimization Focus Shifts from FFN to Attention

Phenomenon: On the FFN side, after DeepSeek successfully ran the large-scale small-expert MoE route, base models gradually converged to highly sparse MoE architectures (such as DeepSeek-R1/V3, Qwen3-MoE, Kimi-K2), substantially reducing inference computation. However, as the context length breaks through 1M, the computational and storage complexity of Attention becomes the new demon, making Attention optimization the new main battlefield.

Attention optimization is mainly KV cache compression. DeepSeek’s MLA compresses per-token KV along the head dimension to the extreme; as a result, compression along the token dimension becomes the new battleground. Currently, there are two main routes for token-dimension compression: 1) Sparse attention: KV is still stored, but access is compressed, i.e., each token only interacts with a small subset of the most important KV, reducing computation and memory bandwidth (e.g., DeepSeek-V3.2’s DSA). 2) Linear attention: Compress dependency on history into a recursible state, making Decode closer to constant per-token overhead (e.g., Qwen3-Next, Kimi Linear). These two routes can be mixed to create hybrid attention. Other token-dimension compression techniques exist, such as compressing KV for consecutive tokens together, but we have not seen mature models using them yet.

Challenges: When the model’s Attention structure changes, it inevitably impacts the implementation of the inference system; system bottlenecks may shift, and some modules may need redesign. For example, we found that after dynamic sparse attention eliminates most Attention computation, the bottleneck of Decode throughput shifts from HBM bandwidth to HBM capacity (KV must remain resident; batch size is more easily bound by capacity). Another example is that when using linear attention, the model state is no longer a complete per-token KV cache but an SSM maintained per layer; therefore, traditional “prefix KV reuse-style Context Caching” needs to evolve into “SSM checkpoint/restore.” In hybrid structures, the system must manage two types of state objects simultaneously: KV cache + SSM. Caching, routing, and memory orchestration all become more complex.

II. Systematic Layout of Inference Technology Innovation (Overview)

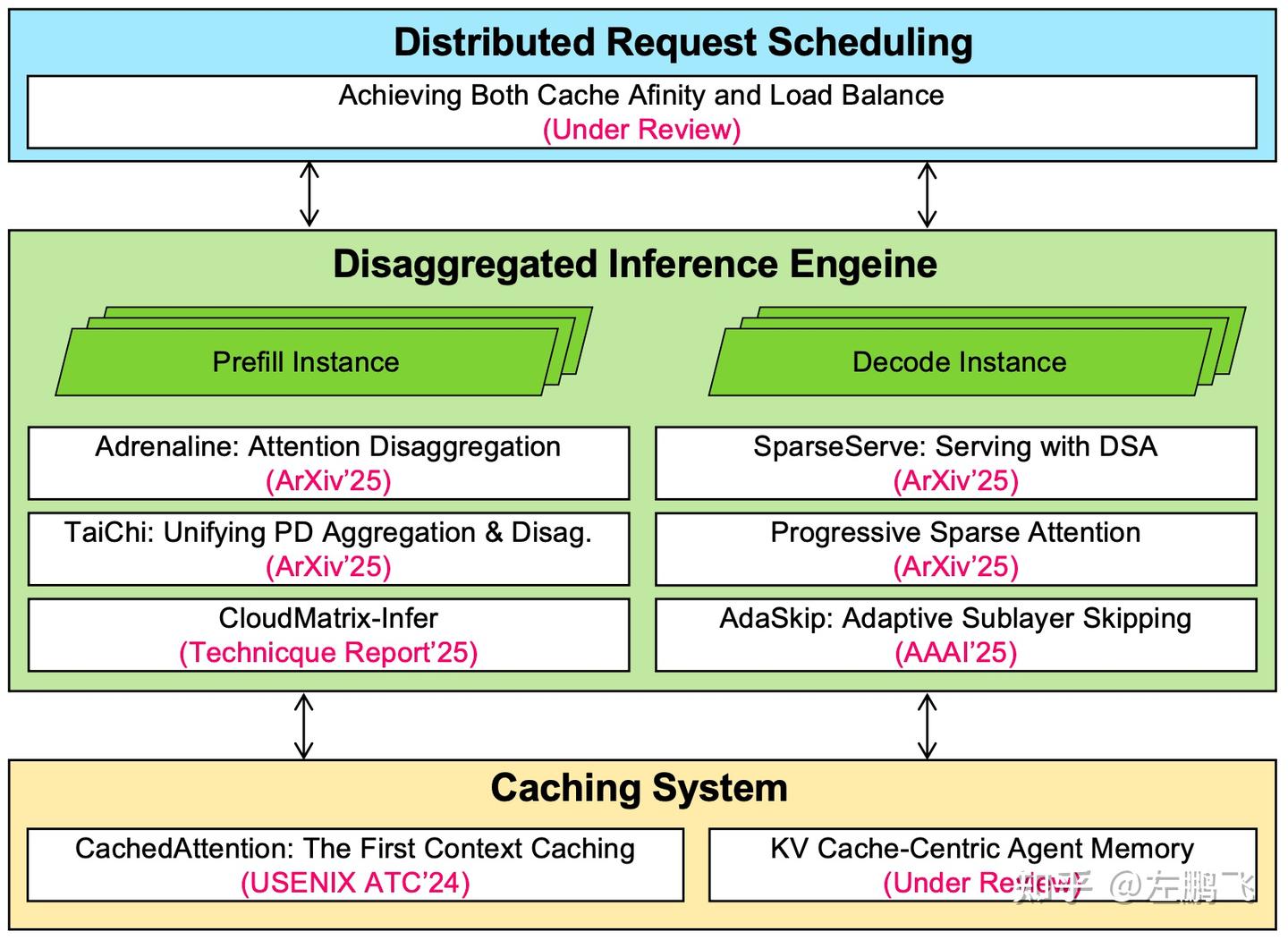

To transform the above “trends” into concrete research topics, we narrowed the problem space of LLM inference systems into a three-layer architecture: covering the full chain from bottom-level cache management, mid-level engine optimization, to top-level distributed scheduling. In 2025, our team conducted a comprehensive and systematic layout across these three levels.

Figure 2: Our Team’s Layout of Inference System Technology Innovations As shown in Figure 2, our research covers the complete chain:

Figure 2: Our Team’s Layout of Inference System Technology Innovations As shown in Figure 2, our research covers the complete chain:

Distributed Scheduling Layer: responsible for global request scheduling. The core challenge is, in a stateful service system, how to balance locality and load balance. We proposed DualMap (Achieving Both Cache Affinity and Load Balance), which breaks the traditional either-or dilemma through double hashing and state-aware routing inspired by The Power of Two Choices. Inference Engine Layer: responsible for efficient execution of model computation. In response to the resource utilization mismatch after PD separation, we introduced Adrenaline (Attention Disaggregation), which simultaneously improves resource utilization of P and D through attention disaggregation and mixed colocation; and TaiChi, which unifies the architectural debate between PD aggregation and separation, and squeezes resources on SLO-over-satisfied requests to improve overall throughput. In addition, for the HBM capacity bottleneck of dynamic sparse attention (DSA) models, we introduced SparseServe, scaling batch size to improve Decode throughput. Caching System Layer: responsible for the storage and reuse of KV cache. For this layer, we published CachedAttention at USENIX ATC ‘24, which is likely the first top-conference paper on Context Caching systems, and we pioneered the use of hierarchical storage for KV cache. In 2025, for the Agent scenario, we further evolved into KV Cache-Centric Agent Memory (MemArt), revolutionizing the representation of Agent memory. These three layers, through tight vertical co-design, together constitute our answer to inference-system technical innovation.

III. Five Representative Works in 2025

Next, I will briefly introduce the content of these five representative works. Interested readers can further read the original papers.

1) SparseServe: Breaking the “Capacity Wall” of Dynamic Sparse Attention

Paper link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.24626v1

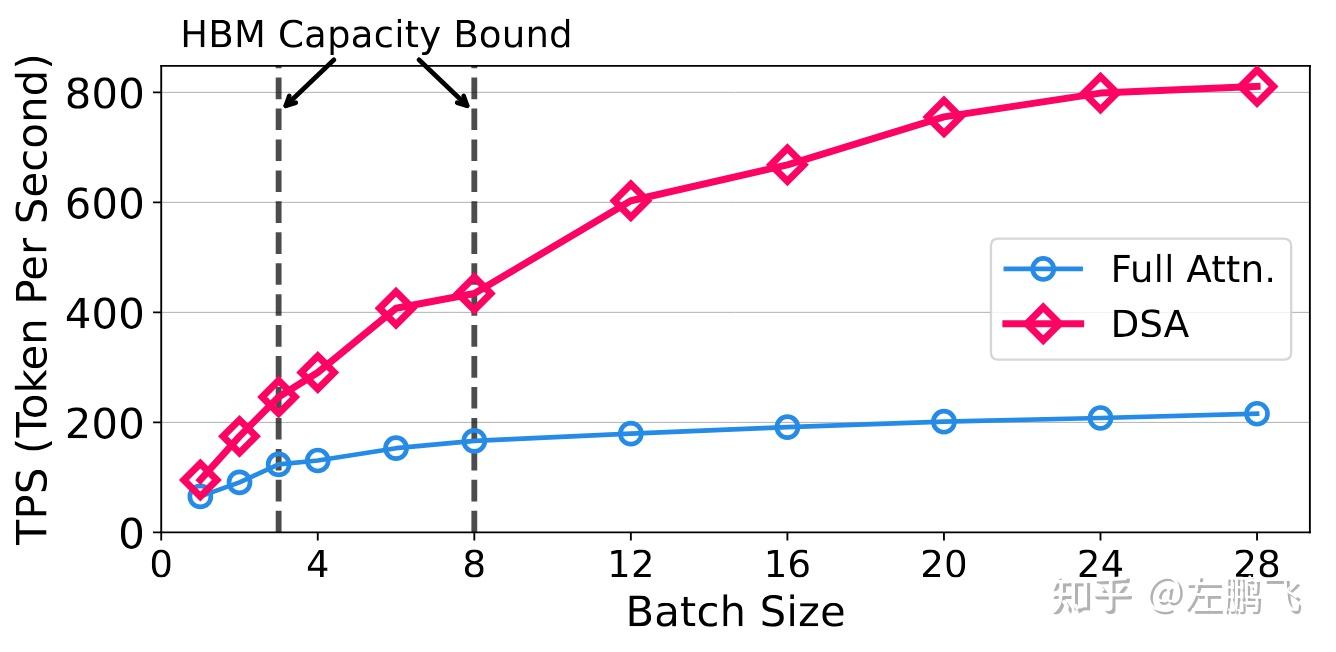

Motivation: Introducing dynamic sparse attention (DSA) dramatically reduces Attention computation and per-step memory access. However, the system faces a severe “storage efficiency paradox”: to guarantee low decoding latency, a large number of KV caches corresponding to unselected “cold” tokens must still reside in HBM. This directly shifts the system bottleneck from “compute/bandwidth” to “memory capacity.” As shown in Figure 3, for full attention, limited by the memory bandwidth wall, simply increasing batch size yields saturated improvements to decoding throughput (the curve flattens); whereas for DSA, thanks to its low bandwidth requirements, increasing batch size should deliver a linear jump in end-to-end throughput. Unfortunately, in reality, batch size is often prematurely hard-limited by HBM physical capacity, preventing DSA’s extremely high theoretical throughput ceiling from being fulfilled in production.

Figure 3: Impact of Increasing Batch Size on Throughput of Full Attention and DSA (two HBM capacity lines for 40GB and 80GB A100)

Figure 3: Impact of Increasing Batch Size on Throughput of Full Attention and DSA (two HBM capacity lines for 40GB and 80GB A100)

Core idea: Offloading these underutilized KV caches to DRAM (system memory) can free up HBM capacity, thereby allowing larger parallel batch sizes. However, implementing such hierarchical HBM–DRAM storage brings new challenges, including fragmented KV cache access, HBM cache contention, and the high HBM demands of hybrid batching—all of which remain unresolved in prior work.

To address these challenges, we propose SparseServe, an LLM inference technique designed to unleash the parallel potential of DSA through efficient hierarchical HBM–DRAM management. SparseServe introduces three key innovations: 1) Fragmentation-aware KV cache transfer: accelerating data movement between HBM and DRAM via GPU-direct loading (FlashH2D) and CPU-assisted saving (FlashD2H); 2) Working-set-aware batch size control: adjusting batch sizes based on real-time working-set estimation to minimize HBM cache thrashing; 3) Layer-segmented Prefill: bounding HBM usage during Prefill to a single layer, enabling efficient execution even for long prompts.

Results: By breaking the capacity wall, SparseServe reduces TTFT (time-to-first-token) latency by 9.26× and increases throughput by 3.14×.

2) Adrenaline: Injecting “Adrenaline” into Inference Systems

Paper link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.20552

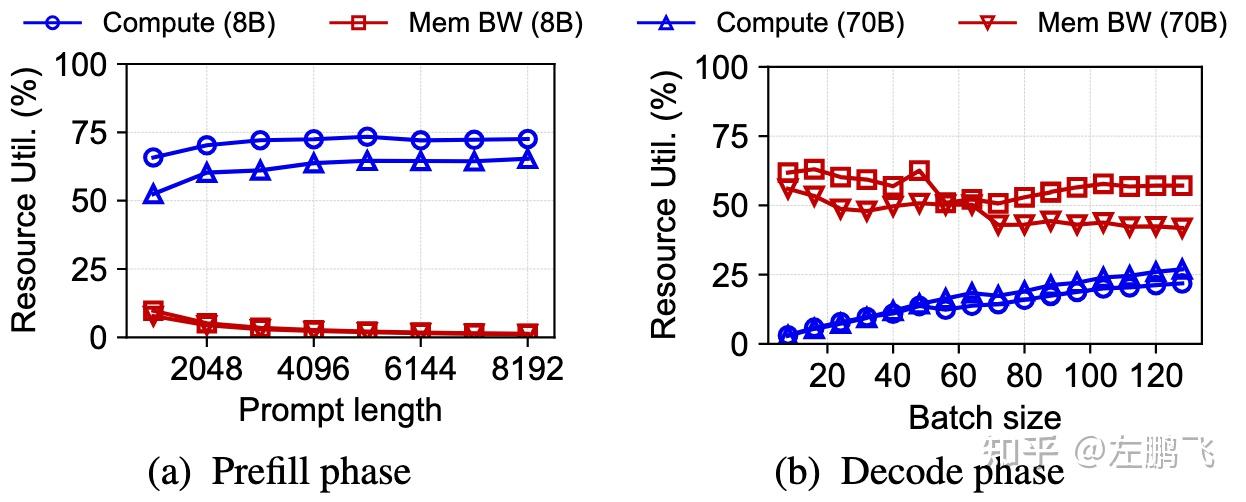

Motivation: In the mainstream PD separation architecture, we face a severe resource mismatch. As shown in Figure 4, the Decode node, limited by HBM bandwidth, often has its expensive compute resources “starved” and cannot be fully utilized; meanwhile, the Prefill node, handling compute-intensive Prefill tasks, has its abundant HBM bandwidth long underutilized. However, physical separation prevents Decode from “borrowing” the Prefill node’s HBM bandwidth, and Prefill cannot “support” the compute needs of Decode. This divide forms “resource islands” between Prefill and Decode nodes, making it difficult to break the bottleneck of overall cluster resource utilization.

Figure 4: Resource Utilization of Prefill and Decode Nodes Under PD Separation

Figure 4: Resource Utilization of Prefill and Decode Nodes Under PD Separation

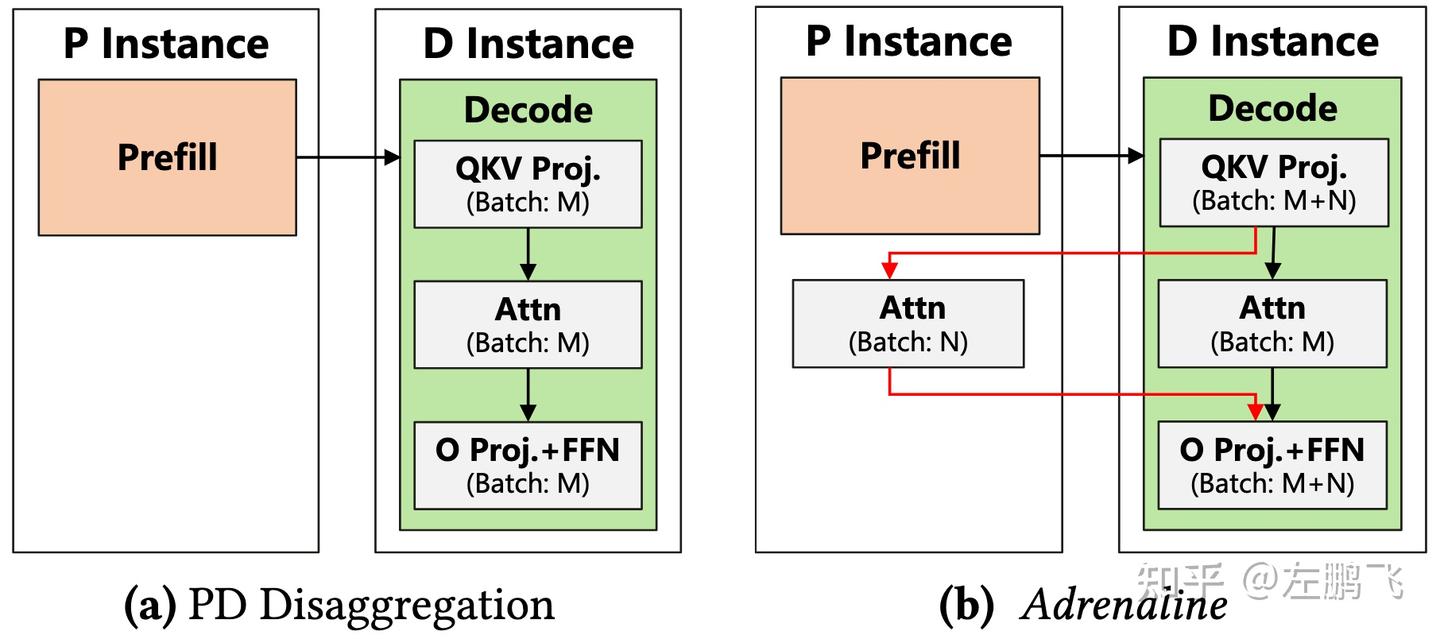

Core idea: To solve this structural imbalance, we propose Adrenaline, an inference service system that realizes “fluid resource pooling.” Inspired by osmosis in biology—solvent naturally passes through a semi-permeable membrane to balance concentration—Adrenaline allows memory-intensive Decode attention computation (and its associated KV cache) to permeate across the physical boundary between Prefill and Decode instances.

By letting Decode attention tasks naturally flow from resource-constrained Decode nodes to HBM-rich Prefill nodes, Adrenaline effectively transforms underutilized HBM on Prefill GPUs into an extended resource pool for Decode tasks. This mechanism successfully balances resource pressure within the cluster: it “feeds” the idle HBM capacity and bandwidth on Prefill nodes while unlocking larger batch sizes on Decode nodes. In addition, Adrenaline overcomes cross-instance latency and interference via low-latency decoding synchronization, resource-efficient Prefill colocation, and SLO-aware offloading.

Figure 5: Comparison of Adrenaline with Original PD Separation Workflow (increasing Decode batch size from M to M+N)

Figure 5: Comparison of Adrenaline with Original PD Separation Workflow (increasing Decode batch size from M to M+N)

Results: Compared to state-of-the-art PD separation systems, Adrenaline increases utilization across different resources by 1.05× to 6.66×, and improves overall inference throughput by 2.04× under SLO constraints.

3) TaiChi: The Tai Chi Way of Unifying Architectures

Paper link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.01989

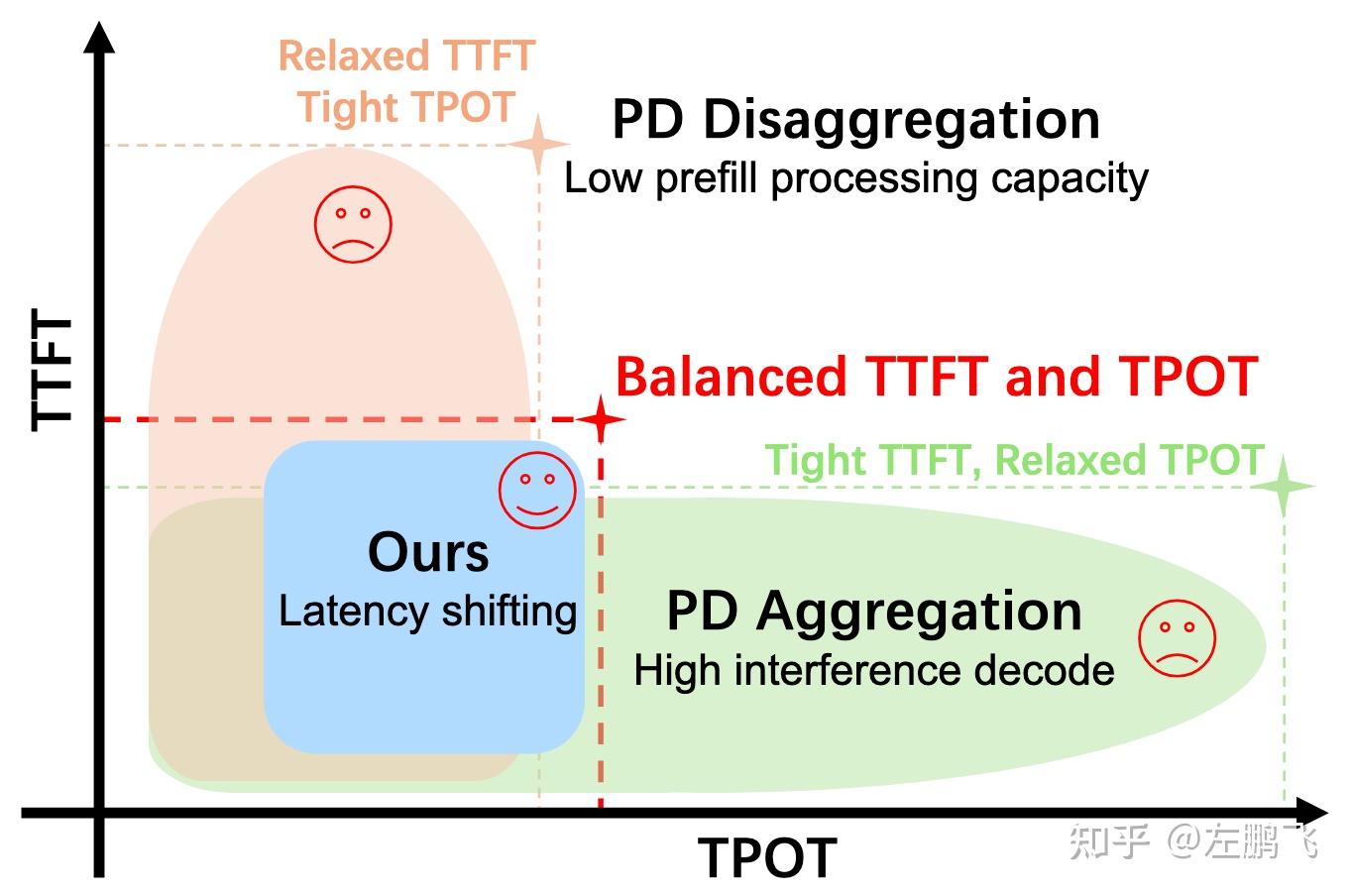

Motivation: In the LLM inference field, there is an architectural debate: one side is PD aggregation (placing Prefill and Decode on the same GPU), while the other is PD separation (deploying them on different GPUs). We systematically compared their performance under different TTFT and TPOT SLOs and found: when TTFT SLO is strict and TPOT SLO is relaxed, aggregation wins; under the opposite conditions, separation is better. However, under balanced TTFT/TPOT SLOs, both show significant suboptimality in terms of Goodput (effective throughput under SLO), revealing a previously uncharacterized “Goodput Gap,” as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: TTFT and TPOT distributions under different scheduling strategies, with the same number of compute nodes and QPS

Figure 6: TTFT and TPOT distributions under different scheduling strategies, with the same number of compute nodes and QPS

Core idea: We attribute this Goodput Gap to underutilized Latency Slack: many requests finish far below their TTFT/TPOT SLOs while other requests face SLA violation risk; yet current systems only expose unified, stage-level knobs and cannot reallocate slack across requests and stages. Therefore, we propose Latency Shifting as a design principle for LLM serving: treat TTFT/TPOT SLO slack as a core resource, strategically reassign it to maximize Goodput.

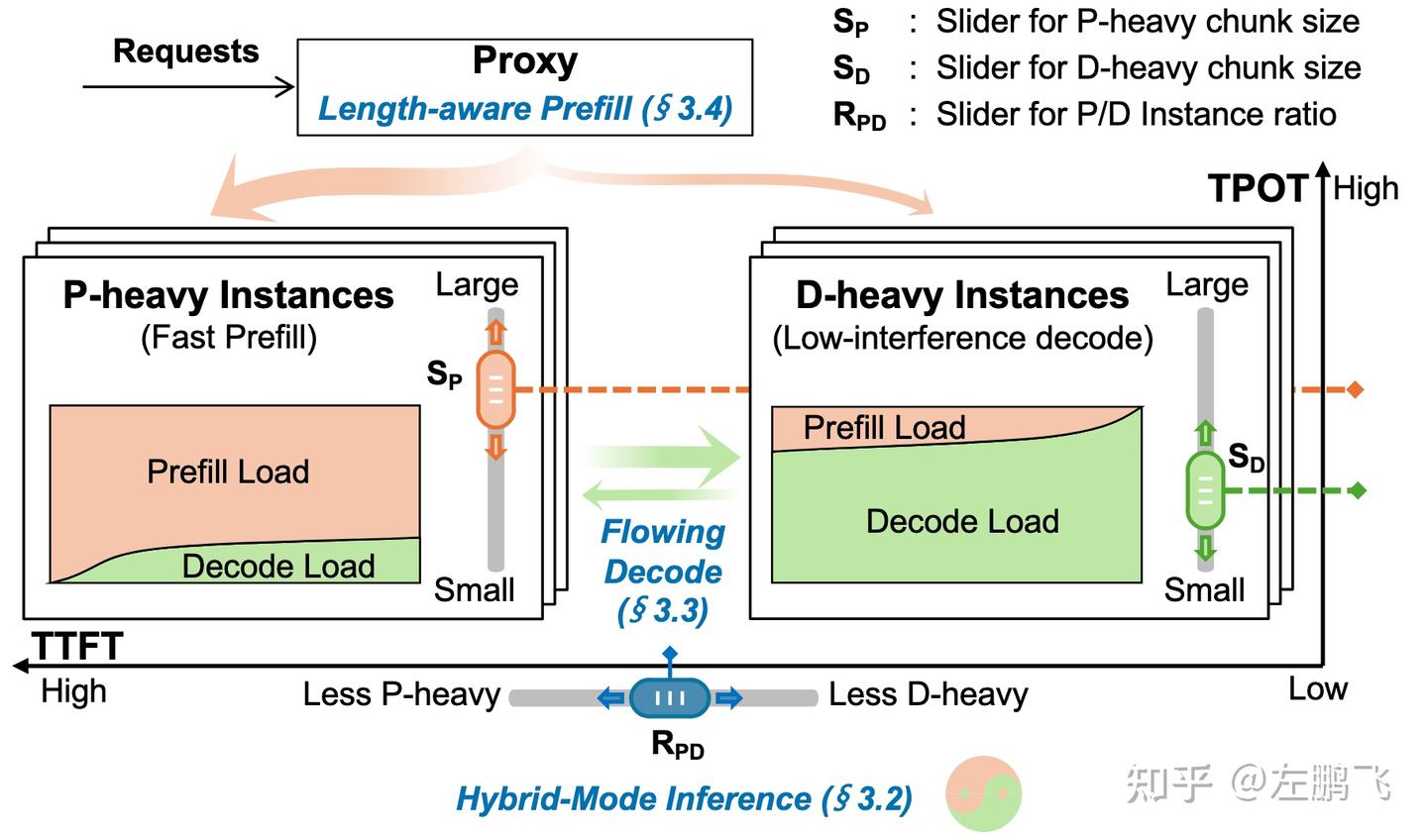

To realize this idea, we propose TaiChi, an LLM serving system that achieves Latency Shifting via hybrid-mode inference architecture and two request-level schedulers. Hybrid mode, operating on heterogeneous Prefill-heavy and Decode-heavy instances, combines “aggregated batching” with “per-request stage decoupling” to fill the blanks in the 2D PD design space. On this basis, Flowing Decode shapes TPOT under constraints of batched decode and unknown output lengths, while Length-aware Prefill selectively “downgrades” Prefill on requests with abundant TTFT slack according to TTFT prediction. Finally, through the design of three sliders, TaiChi unifies PD aggregation, PD separation, and hybrid-mode inference under a single architecture, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: TaiChi architecture unifying PD aggregation, PD separation, and hybrid-mode inference

Figure 7: TaiChi architecture unifying PD aggregation, PD separation, and hybrid-mode inference

Results: Compared to state-of-the-art PD aggregation and separation systems, TaiChi improves Goodput by up to 40%, reduces P90 TTFT by up to 5.3×, and reduces P90 TPOT by up to 1.6×.

4) DualMap: Achieving Both Affinity and Balance in Distributed Scheduling

Paper link: To be supplemented

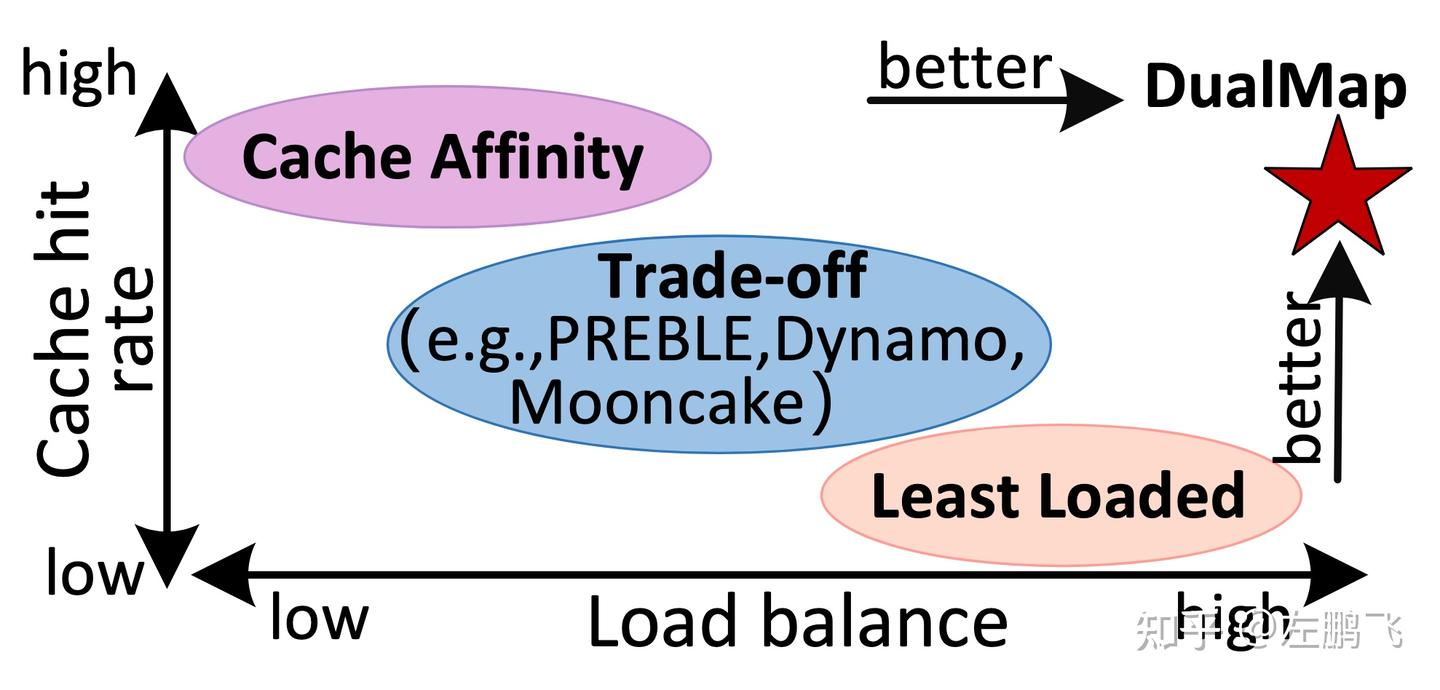

Motivation: In LLM inference services, reusing prompt KV cache across requests is key to reducing TTFT and service cost. Cache-affinity scheduling aims to colocate requests with the same prompt prefix to maximize KV reuse; however, this often conflicts with load-balancing scheduling, which aims to evenly distribute requests across instances. Existing schedulers struggle to reconcile this trade-off because they typically operate in a single mapping space, applying affinity routing to some requests and load balancing to others, lacking a unified scheme for achieving both goals simultaneously.

Figure 8: DualMap vs. existing work on cache affinity and load balancing

Figure 8: DualMap vs. existing work on cache affinity and load balancing

Core idea: To overcome this limitation, we propose DualMap, a dual-mapping scheduling strategy for distributed LLM serving that simultaneously achieves cache affinity and load balancing, as shown in Figure 8. The core idea is: based on the request’s prompt, use two independent hash functions to map each request to two candidate instances, then intelligently select the better one based on the current system state. This design leverages The Power of Two Choices, increasing the probability of colocating requests with shared prefixes while also ensuring that requests with different prefixes are evenly spread across the cluster.

To keep DualMap robust under dynamic and skewed real-world workloads, we introduce three techniques: SLO-aware request routing: prioritize cache affinity, but switch to load-aware scheduling when TTFT exceeds SLO, enhancing load balancing without sacrificing cache reuse; Hotspot-aware rebalancing: dynamically migrate requests from overloaded instances to low-load instances to eliminate hotspots and rebalance the system; Lightweight dual-hash-ring scaling: support fast, low-overhead instance scaling using dual-hash-ring mapping, avoiding expensive global remapping. Results: Compared to state-of-the-art work, under the same TTFT SLO constraint, DualMap increases the system’s Effective Request Capacity by up to 2.25×.

5) KVCache-Centric Memory (MemArt): Native Memory for Agents

Paper link: To be supplemented

Motivation: LLM agents are becoming a new paradigm for applying base models to complex real-world workflows, such as scientific exploration, programming assistants, and automated task planning. Unlike single-prompt or short-dialogue bots, agents often run for hours to days, involve dozens to hundreds of iterative calls, and quickly accumulate context that exceeds the model’s context window. To address this scalability bottleneck, the industry has begun introducing external memory systems to store and retrieve historical information on demand, maintaining efficiency, accuracy, and robustness in long-horizon tasks.

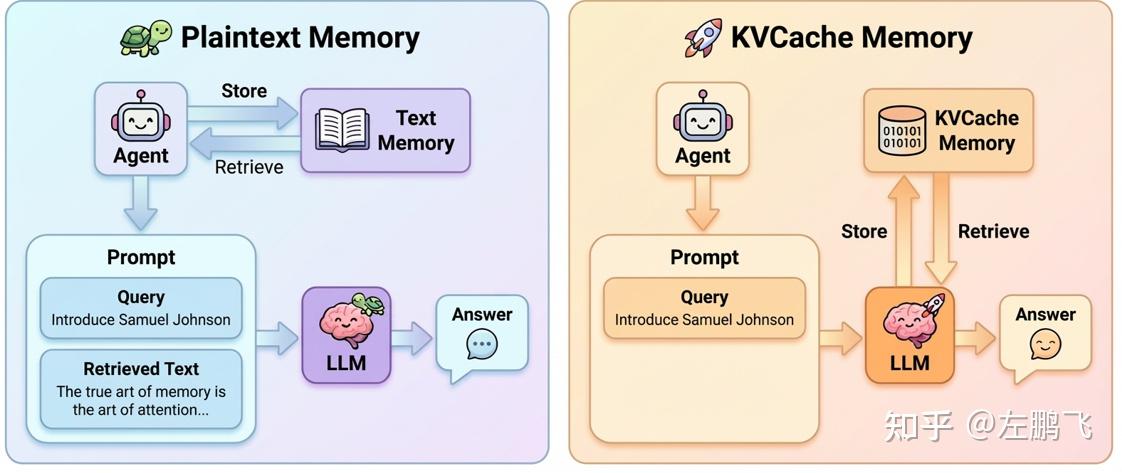

Currently, most mainstream memory systems adopt “plaintext memory”: they segment/summarize historical dialogues into entries, then retrieve using a vector database or graph structure. This approach has two fundamental problems: (1) summarization and similarity-based retrieval struggle to preserve the complete semantic dependencies of multi-turn interactions, easily missing key information or introducing noise, and often perform worse than full-context reasoning; (2) discrete memory entries break the continuous structure of the prompt prefix, undermining the inference engine’s reliance on prefix caching and thereby weakening performance and efficiency benefits.

Figure 9: Workflow comparison between MemArt’s KVCache-centric memory and plaintext memory

Figure 9: Workflow comparison between MemArt’s KVCache-centric memory and plaintext memory

Core idea: We propose MemArt, a new memory paradigm: shifting from plaintext memory to KVCache-centric memory, improving both inference effectiveness and efficiency. MemArt stores historical context directly as reusable KV blocks and computes attention scores between the current prompt and each KV block in the latent space to retrieve relevant memory, as shown in Figure 9. It offers three advantages: (1) High-fidelity retrieval: aligned with the model’s attention mechanism, yielding more accurate semantics; (2) High efficiency: KV blocks that hit can be reused directly in Prefill, avoiding reprocessing tokens, reducing latency and cost; (3) Easy integration: plug-and-play without changing model weights or structure.

There remain two major challenges to implementing KVCache-centric memory: First, as the memory repository grows, how to avoid scanning everything while still retrieving accurately; second, retrieved KV blocks are usually non-contiguous and carry original positional information—direct concatenation causes positional inconsistency, affecting output quality. To this end, MemArt constructs a compressed representative key for each KV block for fast screening; then uses a multi-token aggregation strategy to combine attention scores across all prompt tokens, improving relevance. Finally, it verifies and adjusts the positions of retrieved blocks via a decoupled positional encoding mechanism, enabling safe, coherent reuse in the current context.

Results: Compared to state-of-the-art plaintext memory methods, MemArt improves inference accuracy by 11.8%–39.4%, approaching full-context reasoning performance. More importantly, compared to plaintext memory methods, MemArt reduces the number of Prefill tokens by 91–135×.

These results suggest that KVCache-centric memory may become the key foundation for building high-accuracy, high-efficiency, long-context LLM agents. Meanwhile, it introduces a series of system implementation challenges, especially storage capacity and cost pressure as memory scale increases: hierarchical storage (HBM/DRAM/SSD), efficient cache management strategies, and KV cache compression and eviction are needed for sustainable engineering deployment. For those interested in this direction, a promising path is “lower-cost KV-level memory management.”

IV. Conclusion

In 2025, our team’s main research line was very clear: no longer confined to single-operator or single-model optimization, but advancing end-to-end, full-stack system architecture innovation to break down the “resource walls” and “efficiency walls” obstructing inference efficiency.

From SparseServe’s breakthrough on the memory capacity bottleneck of dynamic sparse attention (DSA), to Adrenaline’s ingenious bridging of “resource islands” created by PD separation; from TaiChi putting an end to the architectural route debate between aggregation and separation, to DualMap mathematically reconciling the contradiction between cache affinity and load balancing, and finally to MemArt sinking agent memory from the application layer plaintext into system-level primitives—these works together form a new infrastructure for large-model inference.

BTW: The innovative research results introduced in this article mainly come from my intern team, and I thank them for their outstanding work. We also welcome more excellent students to contact us for internships! In addition, beneath the iceberg, our engineering team has accumulated more highly valuable system practices in production environments, which are not elaborated here due to compliance and space limitations.

Looking Forward to 2026:

If 2025 was a year of system architecture reshaping, then 2026 will be a year where “model evolution and application explosion force a paradigm shift in systems.”

We foresee that model architectures will move towards extreme dynamic sparsity. The deep fusion of MoE and sparse/linear attention heterogeneous compute graphs will drive inference loads to unprecedented levels of dynamism. The full explosion of multimodal capabilities means input streams will extend from text to audio-video streams, bringing heterogeneous context pressure several times larger than today. The further boom of Agent applications will push inference from single-shot interactions to long-horizon, complex-state task orchestration. Another direction of note is Continual Learning, which is likely to become mainstream in the future, but in the short term still faces algorithmic breakthroughs before commercial adoption.

Facing these changes, we will continue to “seek certainty amidst uncertainty”: turn extreme sparsity on the model side into system-side SLO-goodput that is predictable and deliverable; converge multimodal heterogeneous inputs into unified adjustable scheduling and resource orchestration primitives; internalize complex Agent states into reusable, low-cost, governable system-level memory. We look forward to pushing inference infrastructure from “high performance” toward “high adaptability, high reliability, and sustainable scalability,” providing a truly scalable foundation for the next generation of AI applications.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: